The other day I took the decision to delete my Facebook account.

The other day I took the decision to delete my Facebook account.

There has been a lot about Facebook and privacy in the tech press over the past few weeks – making live chats public, the ABC bug, criminalising violations of their terms of service, etc.

Facebook has a clear habit of leaking data, and a general disdain for their user’s privacy. As we can see by the changes to their Terms of Service and default privacy settings over time this is a deliberate strategy, which makes perfect sense since Facebook’s entire business model depends on their users sharing everything.

There’s a problem here of course, because even if you delete your account or were never on Facebook to begin with, the chances are you still are on Facebook.

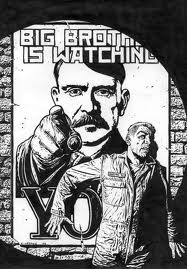

Crowd sourced surveillance

Facebook crowd sources its intelligence gathering by encouraging your friends to continually update it with fairly sizable amounts of information about you, even if you are not a member. The simplest example of this would be the invite system… Facebook user Alice uses the Facebook interface to invite Bob, who is outside of Facebook, to a party… innocuous at first glance, until you consider that Alice has just told Facebook (and by extension: advertisers, government agencies, application developers etc) that Alice knows Bob (expanding the social graph) and has informed them of Bobs email address.

Image tagging presents another interesting problem. Facial recognition has reached a stage where by a machine can tell whether a face belongs too the same person from picture to picture. This feature was included in the latest version of iPhoto for example, but even without facial recognition, a tagged photo provides confirmation that a group of people were together at a certain time – and with geotagging enabled – in a certain place.

Facial recogniton is on Facebook now (via a third party app – although I would imagine Facebook will be developing their own version), Google is also following similar lines of research.

Of course, the algorithm can’t know who you are…

… until someone helpfully tags you of course. At which point you can be identified in any image on Facebook and the wider internet.

Governments have access to this technology as well of course (biometric passports anyone?), and we have already seen moves to incorporate this sort of face tracking and recognition technology in the next generation of CCTV cameras allowing automated tracking of people throughout our cities.

Anyone considering wearing a mask or similar as an obvious countermeasure should take note that the wording of the “burka ban” law recently passed in Belgium… which does not specifically ban the burka, rather bans any clothing that conceals the wearers identity. French and German MEPs are pushing for similar laws throughout the EU.

… first they came for the hoodies, then they came for the Muslims…

Question of ownership

I could easily be accused of being paranoid, but all this is perfectly possible and is an extrapolation of current trends. It also serves to underline two central problems; first, that information is collected and added about you regardless of you do, and second, that this data is not considered to be yours – leading to unintended outcomes should the people holding the data change how they use it.

So much data is collected about you through the usage of online systems. Facebook in particular has extended this intelligence gathering capability out into the wider internet with its seemingly innocuous “like” button, or by secretly installing applications (which have full access to your profile) when you visit Facebook enabled websites (decidedly less innocuous).

Each bit of information gathered is fairly harmless on its own, but when aggregated over time present an incredibly detailed picture of your life – online and offline.

This information is packaged and sold.

That this data doesn’t belong to the person its about – even if it is of a deeply personal nature – is, I think, a rather corrosive assumption. Unfortunately we see this assumption at work all over the place both in government and the private sector, and although I’ve focussed particularly on Facebook in this post, it is only one part of a much wider problem.

Question of control

Fundamentally if you don’t own your data, you can’t possibly control what is done with it. Privacy controls and the like are at best a comforting placebo.

For this reason, I am suspicious of “free” services as money must be being made somewhere, and if it is not a direct fee then where?

So how can you keep control?

This is actually a very hard problem, because the obvious solution – not using the services in the first place – increasingly handicaps you.

Facebook has made a push to become the social architecture of the web with their “like” button, which isn’t the end of the world. However, more and more sites are using Facebook, Twitter etc for logon. Linking sites around the internet together and forming a more complete picture of your online habits.

If I want to use Microsoft’s online word processor Docs.com, my only option is to sign in with Facebook. Google docs needs a google account etc..

As Twitter, Facebook and Google etc all compete to be “You” on the internet you will see this kind of thing happening more and more.

Can I live without these services? Possibly. But what if a client uses them to share a specification document, can I refuse to view it? I guess it depends on how understanding your client is.

Is privacy dead?

Privacy is important, and anyone who says that “if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear” should be encouraged to read Anne Frank’s diary.

However, we now live in a world were both online and offline we are encouraged to give away more and more of our private information. What information we don’t give away is obtained by monitoring our actions or provided by others – “Marcus was so wasted at Dave’s party last week, look here’s a picture of him passed out on the floor! LOL”

So much of this is out of your control, and what data is generated is not yours, but at the moment you still have a little wiggle room – if only because all these systems are still rather fragmented.

However, I believe that privacy is going to be one of the main societal battle grounds of the 21st century, and the first salvos have already been fired.

Privacy may not be quite dead yet, but it is certainly missing in action.

Image from ICanHasCheezburger

In the middle of the most drastic budget cuts since the great depression, with billions being slashed from education and welfare, the Interception Modernisation Programme is coming back to life like some horror movie monster.

In the middle of the most drastic budget cuts since the great depression, with billions being slashed from education and welfare, the Interception Modernisation Programme is coming back to life like some horror movie monster.