Two factor authentication (also known as 2FA), is a mechanism to provide extra security to website accounts by requiring a special one time use code, in addition to a user name and password.

This code is typically generated by a hardware dongle or your phone, meaning that you must not only know the password, but also physically have the code generator.

I thought it would be cool if Known had this capability, and so I wrote a plugin to implement it!

How it works

Once the plugin is installed and activated by the admin user, each user will be able to enable two step authentication through a menu on their settings page.

Enabling two factor will generate a special code, which can be used to generate time limited access tokens using a program such as the Google Authenticator. To make setup easier, the plugin generates a special QR code which can be scanned by the reader.

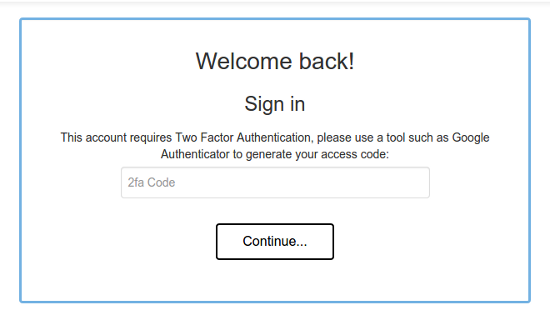

From then on, when you log in, you will get an extra screen which will prompt you for a code.

Enter the code produced by your authenticator and you will be given access!

» Visit the project on Github...

Webhooks are a simple way to glue disparate web services together using standing HTTP protocols in an easy to build for way.

Webhooks are a simple way to glue disparate web services together using standing HTTP protocols in an easy to build for way.

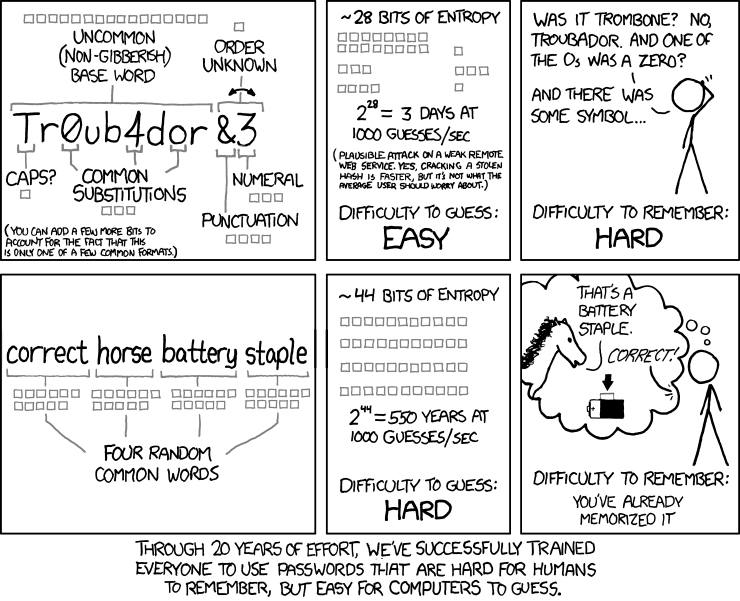

This is just a quick post to nudge you towards a little plugin I wrote for Known which enforces a minimum password strength for user passwords.

This is just a quick post to nudge you towards a little plugin I wrote for Known which enforces a minimum password strength for user passwords.